On this, the second day of its annual developers conference, Microsoft is focusing on enhancements to its Visual Studio software development toolkit to assist in the creation, publication, debugging, and porting of Windows apps. That will be immeasurably helped, Microsoft executives said, by the company’s shift to “universal apps” that share common code between the Windows, Windows Phone, and Xbox platforms.

Microsoft’s Scott Guthrie, on stage at the Microsoft Build conference.

But the cloud also has another purpose: cloud computing. Microsoft’s Azure service already allows developers to spin up virtual machines and SQL databases, and to host websites in the cloud. But in today’s demonstration, executives also showed off what could be a capability in future games: blowing stuff up using a cloud-based physics engine instead of relying on a local machine’s hardware resources.

Microsoft gave no indication that either the Oculus Rift demo the were about to present or what it called Cloud Assist will ever see the light of day as a full-fledged product. But both point to the power of what Microsoft has running behind the scenes.

Microsoft hosts tens of thousands of servers—stored within modular containers with their own cooling and power—in locations throughout the United States and abroad. These servers do everything from hosting enterprise websites and services, to conducting matchmaking services for the Xbox, to powering cloud services such as Outlook.com.

On Thursday, Microsoft corporate vice president Steve Guggenheimer showed off a virtual scene rendered by the WebGL a programming language on a smartphone; and from there, on a PC. His next trick was much more impressive: By dropping 13 lines of code into the scene using a service called Babylon.js—using the “go big button,” according to his partner, technical fellow John Shewchuk—he enabled the scene to be virtually toured though the Oculus Rift headset.

This scene was rendered in WebGL, just before it was rendered for the Oculus Rift.

“One of the keys to making this work is that we’re able to handle this loop at 200Hz,” Guggenheim said. “Any of the other browsers out there don’t have that capability. But it’s also the speed of the PC ecosystem” the USB peripherals, the development tools, that let developers create these experiences with an incredibly low amount of effort, Guggenheim said.

Thunder in the cloud

It could be argued that the notion of cloud gaming originated at Microsoft. Steve Perlman, who founded the cloud-gaming company OnLive, oversaw the development of Microsoft’s WebTV set-top box. OnLive changed hands last year, and Perlman left the company.

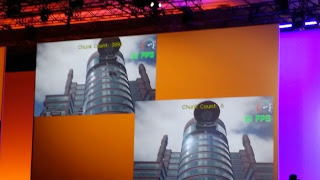

OnLive uses dedicated servers to run demanding 3D games, streaming the action to client PCs over the Internet. Microsoft’s Cloud Assist appears to render physics on Microsoft’s servers, lending realism to the scene without actually controlling it.

Microsoft’s Cloud Assist technology in action.

The demonstration that Guggenheim and Shewchuk showed involved a simulation firing rockets into simulated buildings, which then exploded. The duo showed the scene rendered on a local machine, which crawled along at frame rates in the single digits. They then added Cloud Assist, which improved performance dramatically.

“What we’re seeing is that the power of the cloud makes all things possible,” Shewchuk said.

Post a Comment